Inside The Rise Of Pickleball And Padel In Australia

Illustration: Felix Nankivell

Illustration: Felix Nankivell

A COUPLE OF SUMMERS ago, a group of friends and I arrived at our local tennis court, expecting to take part in what’s become an unofficial national tradition of Australian Open-inspired buffoonery. There, we found two coaches setting up small nets, handing out plastic paddles and chalking makeshift, badminton-sized areas of play into the court. They were there to teach what they called Spec Tennis: a miniaturised version of the real game played with lightweight plastic paddles and deflated balls that fly much like the real thing, but not as far or nearly as fast. Realising it was probably far preferable to a sweaty evening of amateur tennis, we obliged.

The appeal, aside from the Pizza Hut the coaches ordered to lure us back each week, was clear. The small size of the court made the game approachable for a wide range of abilities and fitness levels. The equipment, which allowed you to play different types of shots without fear of sending the ball into another suburb or missing it altogether, made you feel far more athletic than you were. It was fast and frenetic enough to keep the better players engaged, but without sacrificing inclusivity.

Since then, a fresh wave of tennis-adjacent sports has taken over courts and indoor sports centres around the world, combining the intensity and competitiveness of high-level tennis with the accessibility of what, in essence, feel somewhat like backyard games. The two largest, pickleball and padel, are now among the fastest-growing sports in the world (despite both having been around for more than half a century). Both codes are attracting millions of new players, including devotees and investors from the celebrity set (LeBron James, Tom Brady and Michael B. Jordan are among the newly minted owners of American pickleball teams). Both are also undergoing rapid professionalisation and, naturally, rumblings about one of the two becoming an Olympic sport.

Both sports are in a battle to capture as many of these eager new players as they can, poaching swathes of novices from demographics tennis has long tried, and largely failed, to attract. In both Australia and the US, where sunshine and vacant tennis facilities on which to set up makeshift courts are abundant, pickleball looks set to dominate the friendly war between these up-and-coming codes. According to the Australian Sports Commission’s most recent AusPlay study, 92,000 people have actively engaged in pickleball in the last year – already surpassing participation rates in rugby and baseball. Pickleball Australia now boasts 15,000 paying members, a 5000 increase on the beginning of the year.

Many of these new players have been unable – or simply not motivated – to negotiate tennis’s steep learning curve. Older players, particularly, have flocked to the sport in droves. “The sport is easy to learn, but tough to master,” says Pickleball Australia executive officer Brendan Lee. Like many converts, Lee was drawn to the sport after a long career as a tennis coach and player. “You can show up and immediately see progression, and that success breeds enjoyment,” he says. “Whether people tell you they’re competitive or not, we all like to thrive in a competitive space. Pickleball gives anyone a chance to feel that success, whether they want to compete properly or just want to improve in a short amount of time.”

Illustration: Felix Nankivell

Illustration: Felix Nankivell

In Europe and Latin America, padel, which was invented in Mexico but rapidly popularised in Europe during COVID, is currently the sport à la mode. The sport has also built an enviable reputation as a trendy pastime for F1 drivers, famous footballers and even current and former pro tennis players. Currently, it has a reported global player base of more than 30 million people, and that’s only set to grow.

Played in a squash-derived glass enclosure, adding an element of frenetic rebounding into the play, padel devotees preach that the court breeds a level of flair and creativity you simply can’t find in other smaller-format racquet sports. “Being a 3D version of the sport, it’s really a chess-versus-checkers kind of thing,” says Matt Barrelle, the inaugural president of what is now Padel Australia. “It’s competitive, but it’s meditative. You’re present like you would be when surfing, for example. You forget about all your worries for the day while you’re playing.”

Barrelle was one of the sport’s early adopters, having picked the game up during a stint living in Monaco. “We Set up one of the first clubs in the south of France. We’d have tennis pros sneaking out of the Monte Carlo Country Club to come play games, pretending it was part of their workouts. I think that was the second or third club in France at the time. Now there are over 800.

He brought the sport to Australia in 2015, importing two padel courts from Spain and taking over a disused car park in Sydney’s Entertainment Quarter to form the nation’s first padel club. “As it turns out, there were thousands of South Americans and Europeans here, with padel rackets in their hands, ready to go,” he says. “They couldn’t believe that Australia, with so much sunshine and with such a rich tennis history, didn’t have places to play.”

Padel serves as a social outlet not just for these expats, but like pickleball, for former tennis players and people looking for a fun way to get fit. And while the need for purpose-built courts means that padel will likely always be a niche presence in the Australian sporting psyche, the sport’s growth has nonetheless been impressive. There are now 52 padel courts in Australia – a number expected to double over the next year.

Such a pronounced shift in player behaviour has forced the traditional game of tennis to respond. Tennis Australia now governs padel through its Padel Australia subsidiary and has plans to expand its reach in the pickleball space as well. The upcoming Australian Open will play host to both pickleball and padel tournaments for the first time.

While both sports remain a leisure pursuit for 99 per cent of players, part of their joint appeal lies in the lower barriers to entry for those wanting to compete at the highest level. It costs less than $100 to enter a National Pickleball League event in Australia, for instance, where anyone can walk in off the street and compete for prize money.

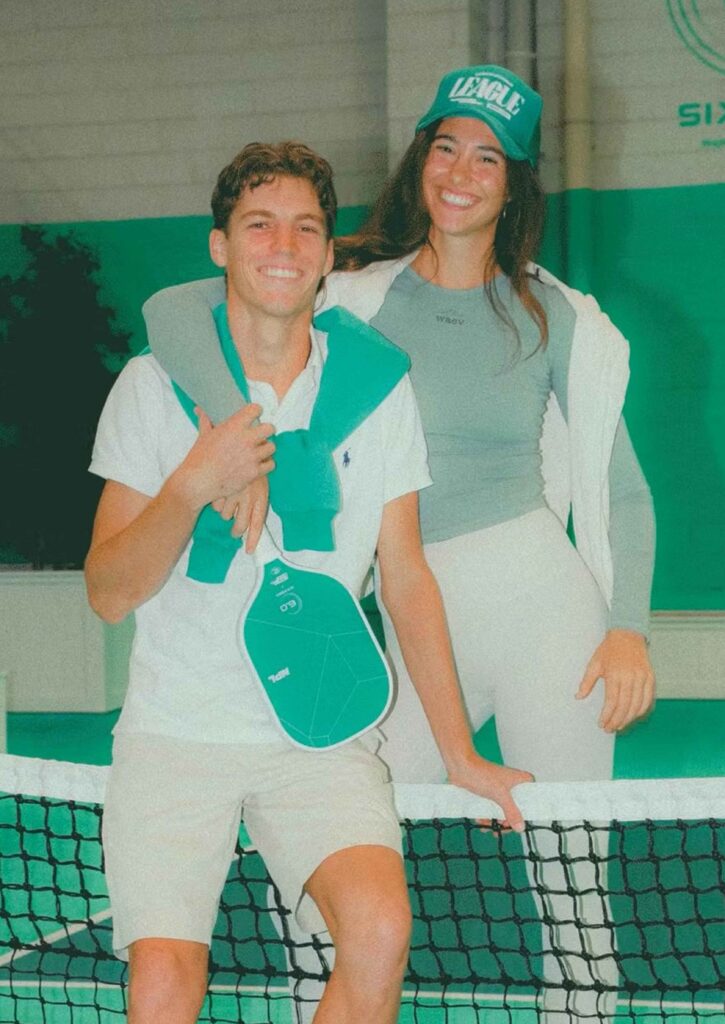

Tom Evans, Australia’s No. 1 Men’s pickleball player, with partner in life and doubles

Tom Evans, Australia’s No. 1 Men’s pickleball player, with partner in life and doubles

Helena Spiridis. Photography: National Pickleball League

As such, even though most of the nation’s best players tend to come from tennis backgrounds, would-be pros in both sports can emerge from almost anywhere. “It’s way, way more diverse,” says 23-year-old Tom Evans, himself a former tennis pro who picked up pickleball around a year ago after withdrawing injured from a tournament on the Gold Coast. He’s now the No. 1 male player in Australia, and ranked fourth in mixed doubles with his partner, Helena Spiridis. “You see people from all backgrounds. There are 50- and 60-year-olds who are still very, very competitive, especially on the doubles court,” he says. “On the other hand, there are kids as young as 14 or 15 who are already approaching a very high level.”

While Evans still splits his time between sport and the business he runs with Helena, he’s part of a growing set of players who hope to go pro before long. Local events in pickleball and padel, which are generally open to all, can offer the chance to earn world- ranking points. Accumulate enough and, in theory, you could qualify for a pro tournament overseas. Evans, having already made his mark accross the US and the Pacific, has his sights set on the Asian leg of the new PWR World Tour, where prize pools at the biggest events are set to exceed $2 million in 2025.

Better known for his larrikin humour and a stint in the I’m A Celebrity . . . jungle than his work with a paddle (for now, at least), Melbourne-based comedian Ash Williams is one of these new everyman hopefuls. Bringing with him the advantage of having been a high- ranked tennis player in his youth, at the age of 42, Williams now hopes to break onto the pro circuit in the next year.

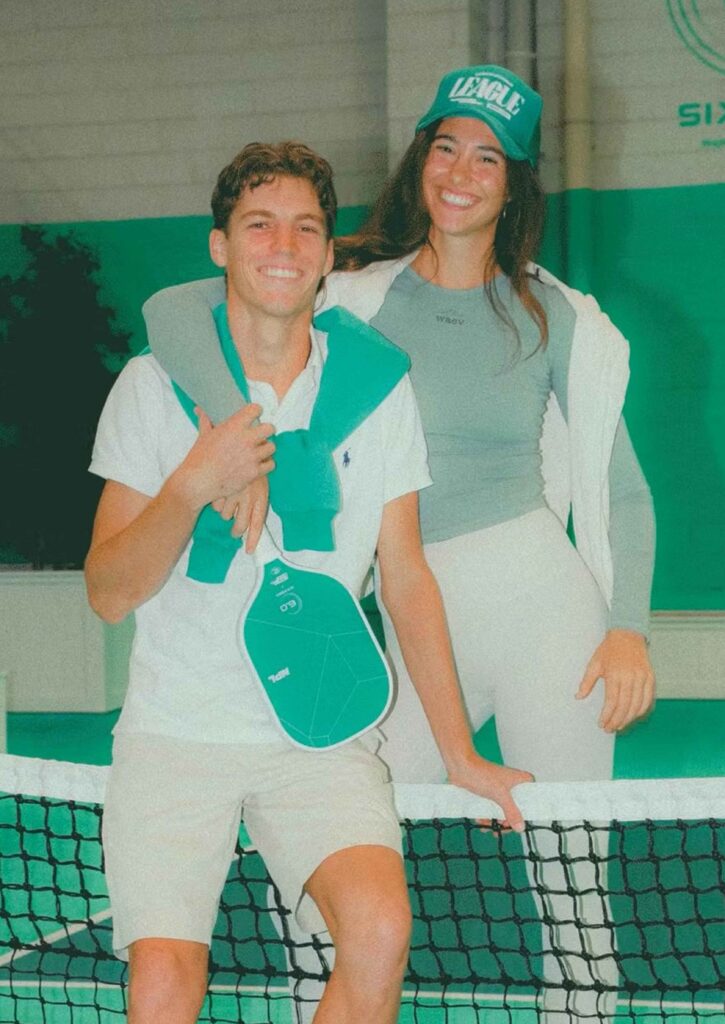

Australian comedian and professional pickleball hopeful Ash Williams.

Australian comedian and professional pickleball hopeful Ash Williams.

“Many of the mates I play tournaments with are just average blokes with jobs and kids,” he tells me. “It doesn’t matter your age or where you come from, you can still play and compete with the best of them. Even the over-50s professional [circuit] is starting to get money behind it. I know blokes in their late 40s who now can’t wait to turn 50 to have a crack at these pro events. It’s giving them an entirely new lease on life.”

There’s a sense of romance that emerges when you talk to devotees of either sport. Each sport has its own vibe – pickleball: playful, casual; padel: cool, cosmopolitan. But for those involved, they’re representative of a new ideal: racquet sports made fun, inclusive and competitive for all, democratised at even the highest levels.

As Williams says, “We’re all still having fun, keeping fit, and chasing the dream”.

Related:

The highest earning tennis players for 2024

Jannik Sinner is on a roll